PRESS RELEASE

Birds

Mar 16 – Oct 1, 2020

Birds

Jonathan Hirschfeld

The main problem with the nature/culture relation is that both terms are untranslatable. From nature’s viewpoint everything is nature. From the bird’s viewpoint the electricity pole is a tree; the cat considers the garbage bin a corpse that found its death in the Savanna. In contrast, culture considers everything to be culture and nothing as natural nature. The bird is a cultural construct and even more so the cat. Nature and culture are simply two completely obscure language games.

Artists have been aware of this forever. The myth of King Midas is about this: every nature he touches turns into culture; beautiful, shinning and endless, unlike the natural apple that is bound to rot, but try eating a golden apple. The myth about Zeuxis whose painting fooled the birds (while he himself was fooled by painting) also tackles this issue. And yet there are strange moments in the history of art in which something does not get lost in translation.

[Image John Constable, Rainstorm over the Sea, ca. 1824-1828]

I am thinking for example about Constable’s insight in parts of his most stunning landscape wherein almost every painterly action can “pass” as sky. This moment is utterly mad. Mad in the sense of the lack of any association between signifier and sign. It is a moment in which a checkers piece appears on a chessboard. Two untranslatable language games find a common and consensual move.

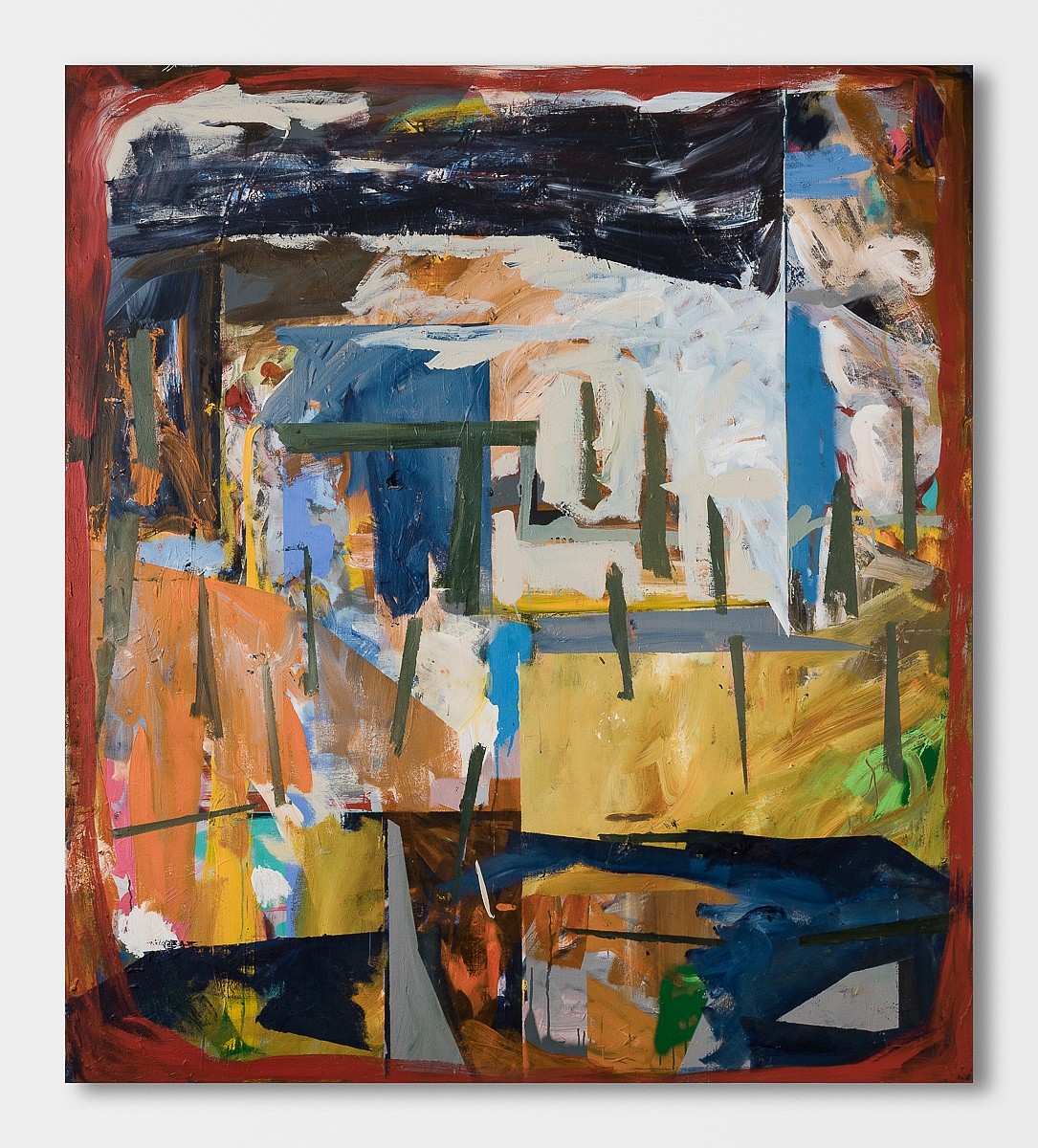

The works in the exhibition, I think, address this moment of searching. They move between the two strategies: abstraction and signification. A person’s most basic act is to gaze up at the stars and see signs, to consider a crow a bad omen. Abstraction is the essential anti-signifying act. Its other extreme is pushing the sign to the limit of meaning and transforming it into a signal. The works in the exhibition are images of nature and culture that suggest momentarily that a bird understands the meaning of the electric pole. That the ornithologist perceives the bird beyond the thousands of cultural screens set before his eyes. Of course he knows the bird’s name: lark, starling or crane, yet at the same time he knows that there is no such thing as “lark,” “starling” or “crane” in nature. It is nothing but a random human conceptualization. Even the concept of species according to types in nature is a collection of individuals who share common features and can create fertile offspring is totally absurd. Indeed the Italian titmouse can procreate with the Swiss and the Swiss with the Austrian and the Austrian with the German but the German titmouse can no longer procreate with the Italian: there is no such thing as “species” in nature, it is an artificial cultural construct of categorizing.

The abstraction of the sky, the trees, of nature itself is a mode of translation. Abstract painting exists in a cultural field, yet it contains something of the incomprehensibility of nature which is, clearly, this: nature says nothing. Simply because it has no author. It lacks intention. It simply is. The medieval world was full of meaning. For example, Saint Patrick, Ireland’s patron saint, is said to have used the shamrock leaf as a metaphor for the Christian Holy Trinity. Lions (whose cubs were believed to be born dead and had to be brought to life by the breath of the father lion) symbolized the resurrection of Jesus. As the world advanced, as the medieval paradigm gradually gave way to that of the enlightenment and rationality – so the world lost meaning. The shamrock no longer signifies anything – it is simply shamrock; lion cubs are merely lion cubs. Modern reason sees the world as it is and not as a symbolic language.

This is, therefore, an exhibition of attempts to arrive at nature, to bypass signifying reason. An exhibition of works by artists who try to make edible golden apples and paintings of birds that can fly.

Installation Photography: Youval Hai.

Photography: Itamar Freed; Youval Hai (Tsibi Geva; Untitled, 2017; Untitled, 2016 by Elad Kopler); Elad Sarig (Untitled, 2018 by Elad Kopler); Ami Erlich Studio A.E (Tamar Roded).